“… this new LiveLab is such a wonderful enhancement to our passion for music and the attendant opportunities for brain understanding.” ~ Judy Marsales

Groundbreaking LIVELab

Tonight’s performance was pretty special. This was the first-ever public concert to be held in the newly built LIVELab, a 100 seat concert hall situated — suspended is the more accurate word –atop the Psychology Building in an architecturally unique sonically isolated box. The venue will be an important research tool for the McMaster Institute for Music and the Mind (MIMM). As we settled in for the concert we would soon be discovering the unique abilities and possibilities of this unique, ground-breaking research facility.

Adding to the excitement was the fact that the world-famous Afiara Quartet was performing.

|

| Eric Wong, Timothy Kantor, Valerie Li, and Adrian Fung are The Afiara Quartet Photo: Daniel Ehrenworth |

Afiara was the perfect ensemble to showcase this first-of-its-kind music research facility. This young ensemble in a few years has traveled the world, establishing a reputation of excellence, and demonstrating a desire to break new ground and create new connections. Their commitment to exploration and innovation is documented in over 25 commissions of new music, new educational outreach initiatives for school children funded by the Ontario ARts Council, and projects with jazz virtuoso Uri Caine, Latin Grammy Award-winning producer Javier Limon, and ground-breaking scratch DJ, Kid Koala.

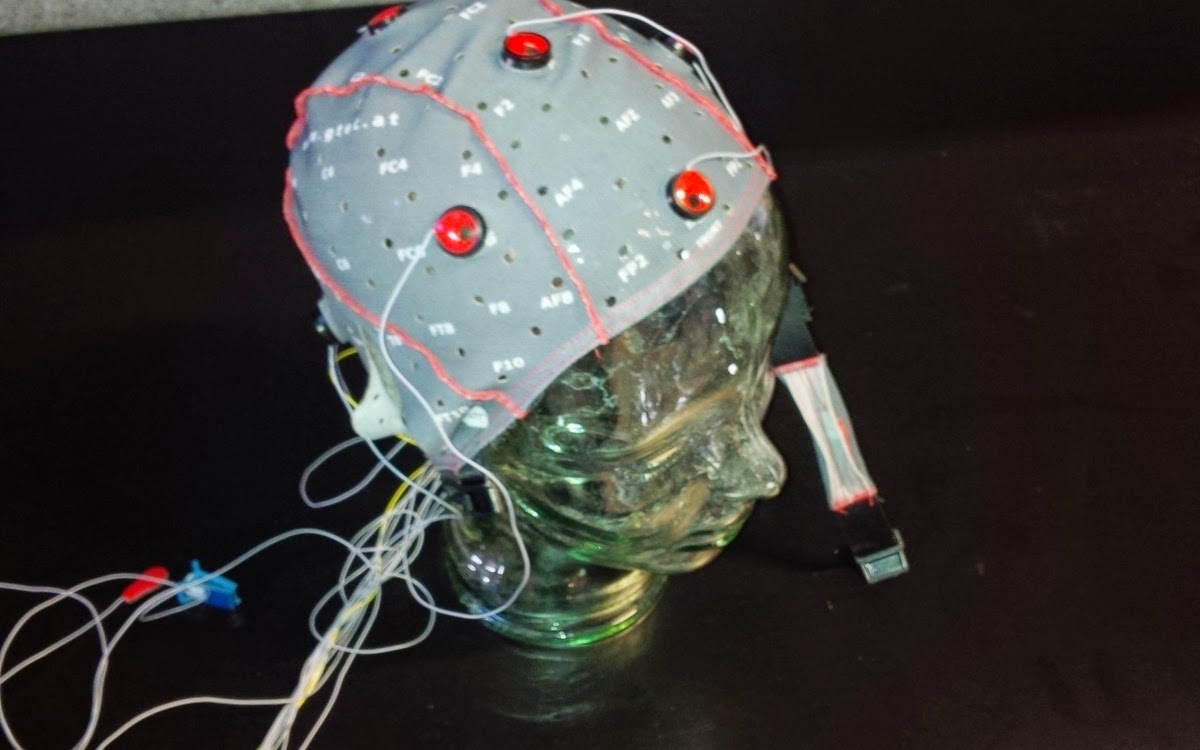

I was taken aback to see violinist Valerie Li and cellist Adrian Fung seated on stage with cloth caps on their heads and bundles of wires draped from them, across a boom stand and into the floor. Looking around I saw reflective spheres stuck on the clothing of violinist Timothy Kantor and violist Eric Wong.

The quartet commendably played excerpts from the unforgiving Beethoven and Mozart quartet repertoire and other music, while demonstrating the type of data the LIVELab is able to collect. First

we watched Li’s and Fung’s brain activity as measured by the EEG caps displayed on a giant screen behind them while playing. My feelings teetered between the guilt of a voyeur and the excitement of a moonwalker. Surely it is fantastic to think that we can now observe a person’s very innermost workings while they make music!

In the next demonstration the reflective spheres allowed an array of infrared cameras in the hall to recreate a 3D wire-frame of their bodies, allowing every body movement to be captured, observed, and measured. Even at this most simple level of observation, I was able to quickly notice that one player’s neck was rigid the whole time, while another’s was fluid and appeared more relaxed. Perhaps an instant clue to the source of a post-performance aching neck?

The final demonstration had everyone in the audience given a tablet that had a slider on it ranging from “calm” to “neutral” to “tension.” As the quartet played we were to move our sliders according to how we sensed the music making us feel, and all of our feedback was averaged into a real-time graph of how the audience was sensing the music and it changed.

The final demonstration had everyone in the audience given a tablet that had a slider on it ranging from “calm” to “neutral” to “tension.” As the quartet played we were to move our sliders according to how we sensed the music making us feel, and all of our feedback was averaged into a real-time graph of how the audience was sensing the music and it changed.

This latter demonstration was remarkable in that we could instantly see the connection between the sound and emotion of the music, and the audience’s reaction. It was also fun to see cellist Adrian Fung try to turn around to look at the screen behind him during the music. Of course, if the musicians had a screen in front of them, there would be all sorts of possibilities, wouldn’t there? For example, do the musicians play with more feeling when they can see the audience response graph, or when it is hidden? What if the audience can’t see the graph, would that make for a different response on their sliders?

It’s also possible to design a different slider which measures a different aspect of the music, or to have different groups of people do the activity and compare the results.

For example, an audience feedback experiment could be performed with volume, or with different degrees of sound sculpting in the room. Different types of reverberation, echo, equalization, and other effects over the full audio range could be controlled, allowing for measurement of audience reactions in different sound environments.

For example, an audience feedback experiment could be performed with volume, or with different degrees of sound sculpting in the room. Different types of reverberation, echo, equalization, and other effects over the full audio range could be controlled, allowing for measurement of audience reactions in different sound environments.

Sound equipment manufacturers will have all kinds of uses for the LIVELab, because it allows new equipment and sound technology to be tested in front of a real audience in an actual performance situation.

And of course, the Afiara Quartet is excited about being able to participate in the kind of research that will give them real-time audience and performer data to inform their onstage behaviour.

Peering into a performing musician’s mind can provide all kinds of new, useful information. It also felt somehow to be a mystical experience. There was a strong feeling of wonder and mystery as one about to enter a room filled with wonderful new discoveries.

We are standing at the doorstep of an exciting new world of brain research, where we can observe and measure the internal workings of musicians’ brains and bodies during performance in an authentic performance setting. It’s time to take “plugging in” to a whole new level!

——————

By Glen Brown